When trying to improve the performance of a Unity iPhone game, time spent reducing the number of draw calls is usually time well spent.

Unfortunately one of the big draw call “hogs” is UnityGUI. A useful guideline is to only use UnityGUI for game menus and option screens where framerate isn’t important. For in-game controls such as a HUD, developers resort to other methods. Alternatives include GUITextures, SpriteManager, or its commercial sibling SpriteManager 2.

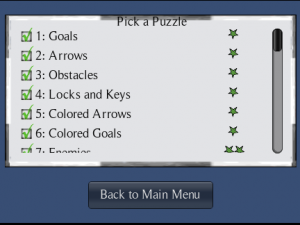

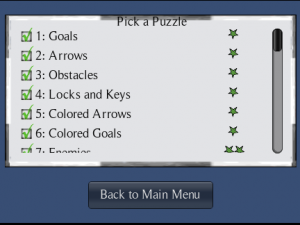

However, other tricks are sometimes possible, and I found an especially easy way to speed up a ScrollView. My game Pawns has a scrolling list that allows the player to pick a puzzle:

Pawns puzzle picker

I used UnityGUI for it, and since the game is not actually being played on this scene I was hoping it would be fast enough. However, the screen was unusably slow on my iPhone, and number of draw calls reported by Unity was 165! So a serious rewrite or redesign appeared to be needed.

The structure of my puzzle picker is a Gui.Window for the frame, containing a Gui.Scrollview. Inside of the scrolling view, I loop through the list of puzzles and paint the three elements that make up each line (a checkbox, text for the puzzle name, and a texture displaying the difficulty rating.) The code looks something like this:

scrollPosition = GUI.BeginScrollView (rScrollFrame, scrollPosition, rList, false, false);

for (int iPuzzle = Puzzles.GetFirstPuzzle(), numPuz = 1;

iPuzzle >= 0;

iPuzzle = Puzzles.GetNextPuzzle(iPuzzle), numPuz++)

{

int difficulty = Puzzles.GetPuzzleDifficulty(iPuzzle)-1;

if ( GUI.Button(rCheckbox, texSolved, checkboxStyle) ||

GUI.Button(rBtn, Puzzles.GetPuzzleName(iPuzzle), puzzleButtonStyle) ||

GUI.Button(rDifficulty, ratings[difficulty], puzzleButtonStyle) )

{

// Code to jump to the selected puzzle goes here...

}

// set up rectangles for the next line

rBtn.y += lineHeight;

rTexture.y += lineHeight;

rDifficulty.y += lineHeight;

}

GUI.EndScrollView();

Each GUI element causes a draw call. (If you are using GUILayout instead of the GUI class, then double that.) The more puzzles in my list, the more draw calls.

For the total number to be as high as 165, even the lines which are currently scrolled off the screen are generating draw calls. On my screen if the player can’t see a line they can’t tap on it, and no code depends on them. In fact, I don’t need to draw them at all. If I was using GUILayout then I wouldn’t know the position of each element, but I’m using GUI, which requires me to position each element myself.

So it turns out it’s a simple matter to skip GUI elements that are not visible. You simply test the rectangle of each control before drawing it. In my case all scrolling is vertical, and the elements are arranged in lines, so I can skip entire lines by testing if either the top or bottom of each line is visible.

The code now looks something like this. Note the line marked *NEW*:

scrollPosition = GUI.BeginScrollView (rScrollFrame, scrollPosition, rList, false, false);

for (int iPuzzle = Puzzles.GetFirstPuzzle(), numPuz = 1;

iPuzzle >= 0;

iPuzzle = Puzzles.GetNextPuzzle(iPuzzle), numPuz++)

{

// *NEW* don't actually draw the controls if this line's rectangle is not visible

if ( rBtn.yMin >= scrollPosition.y && rBtn.yMax <= scrollPosition.y + rScrollFrame.height )

{

int difficulty = Puzzles.GetPuzzleDifficulty(iPuzzle)-1;

if ( GUI.Button(rCheckbox, texSolved, checkboxStyle) ||

GUI.Button(rBtn, Puzzles.GetPuzzleName(iPuzzle), puzzleButtonStyle) ||

GUI.Button(rDifficulty, ratings[difficulty], puzzleButtonStyle) )

{

// Code to jump to the selected puzzle goes here...

}

}

// set up rectangles for the next line

rBtn.y += lineHeight;

rTexture.y += lineHeight;

rDifficulty.y += lineHeight;

}

GUI.EndScrollView();

This worked well; only 6 or 7 lines are ever visible at a time, so the draw calls now hovers around 27 no matter how puzzles are in the list. The screen is now usable on my iPhone, though I should probably cut the number of draw calls a little further.

Obviously not everyone will happen to be using ScrollViews so I'll mention a few general approaches to improve UnityGUI's performance:

- Combine elements/textures. For example, if I painted each line with a single texture instead of three separate elements, that would cut the draw calls by two-thirds. I could go further and paint multiple lines, even entire pages in one texture.

- Avoid GuiLayout. If you don't use GuiLayout at all, and your GUI script sets

[code language="csharp"]useGUILayout = false;[/code] early, such as in the Awake method, then the number of UnityGUI draw calls will be cut in half.

- Redesign. For my example I could have abandoned the scrolling interface and replaced it with page-up/page-down buttons.

I will probably need to try out alternatives such as GUITexture or SpriteManager to speed up my main game screen, so I may have more to say about them at a later date.